A Biblical Focus

Down to the eighteenth century, pastors and theologians regularly considered the concept of beauty to be central to any discussion of the divine nature. As these pastors and theologians read the Bible, especially the Hebrew Scriptures, they were struck by various places where God is described as beautiful. For example, in Psalm 27:4, the Psalmist asserts, “One thing I have desired of the Lord, that will I seek: that I may dwell in the house of the Lord all the days of my life, to behold the beauty of the Lord” (NKJV). Here, beauty is ascribed to God as a way of expressing the Psalmist’s conviction that the face-to-face vision of God is the profoundest experience available to a human being. Again, in Psalm 145:5 the Psalmist states that he will meditate “on the glorious splendor” or beauty of God’s majesty (NKJV). Similarly, the eighth-century (bc) prophet Isaiah can predict that there is coming a day when God will be “a crown of glory and a diadem of beauty” to His people (Isa 28:5, NKJV).

One of the most important biblical concepts in this connection is that of “glory.” When used with reference to God, this concept emphasizes His greatness and transcendence, splendor and holiness. God is thus said to be clothed with glory (Psalm 104:1), and His works to be full of His glory (Ps 111:3). The created realm, the product of His hands, speaks of this glory day after day (Ps 19:1-2). But it is especially in His redemptive activity on the plane of history that God’s glory is revealed. The glory manifested in this activity is to be proclaimed throughout all the earth (Ps 96:3), so that one day “the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord” (Hab 2:14, NKJV). In other words, it was their encounter with God on the plane of history that especially enabled the biblical authors to see God’s beauty and loveliness shining through the created realm.

Augustine and Aquinas on the Beauty of God

Later theologians built upon these biblical foundations. The fourth-century North African thinker Augustine (354–430), for instance, identifies God and beauty in a famous prayer from his Confessions:

I have learnt to love you late, Beauty at once so ancient and so new! I have learnt to love you late! You were within me, and I was in the world outside myself. I searched for you outside myself and, disfigured as I was, I fell upon the lovely things of your creation… The beautiful things of this world kept me from you and yet, if they had not been in you, they would have had no being at all.

The material realm is only beautiful because it derives both its being and its beauty from the One who is Beauty itself, namely, God. Augustine intimates that if he had been properly attendant to the derivative beauty of the world, he would have been led to its divine source.

Similarly, Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225–1274), the quintessential mediaeval theologian, argues that God is called Beauty because, as Aquinas comments, “He gives beauty to all created beings.” He is, Aquinas goes on, most beautiful and super-beautiful, both because of His exceeding greatness (like the sun in relation to hot things) and because He is the source of all that is beautiful in the universe. He is thus beautiful in Himself and not with respect to anything else. And since God has beauty as His own, He can communicate it to His creation. He is, therefore, the exemplary cause of all that is beautiful. Or, as Aquinas puts it elsewhere: “Things are beautiful by the indwelling of God.”

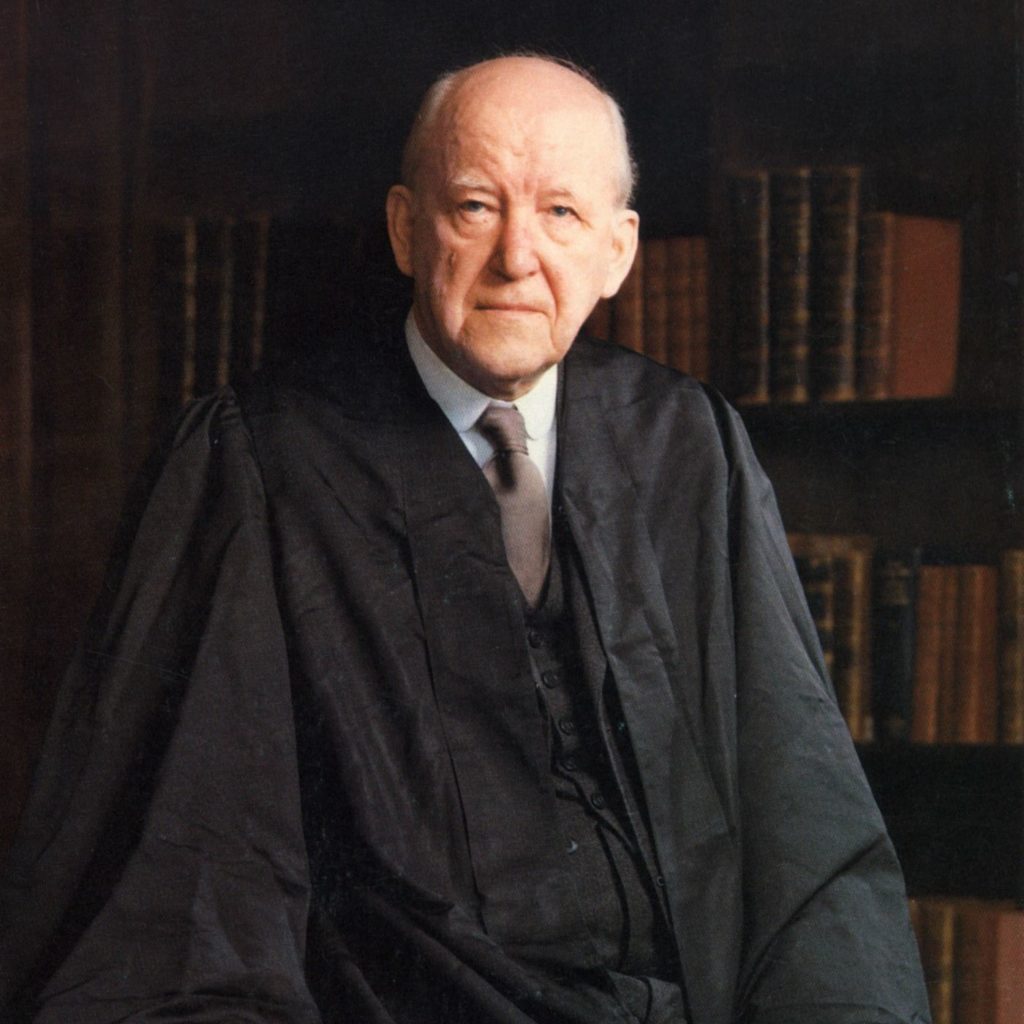

Jonathan Edwards Reflects on the Beauty of God

As one enters the modern era, a profound reconstruction takes place in thinking about beauty in general. The watershed is the eighteenth century, when there is a dramatic movement away from the question of the nature of beauty to a focus upon the perceiver’s experience of the beautiful. The perception of beauty now becomes the basic concept in the writing and thinking about this subject. And it is intriguing that there is a corresponding diminution of interest in the ascription of beauty to God. Nevertheless, one can still find vital representatives of the older tradition. One such figure is the New England theologian, Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758), who stands at the center of eighteenth-century Evangelical spirituality and who was deeply conversant with earlier theological thought, especially that of the Augustinian tradition. There is no doubt that beauty is a central and defining category in Edwards’ thinking about God. He regards beauty as a key distinguishing feature of the divine being: “God is God,” he writes in his Religious Affections, “and distinguished from all other beings, and exalted above ‘em, chiefly by His divine beauty, which is infinitely diverse from all other beauty.” Unlike creatures who receive their beauty from another, namely, God, it is “peculiar to God,” Edwards writes elsewhere, “that He has beauty within Himself.” Typical of the older tradition in aesthetics, his central interest is not in what he calls “secondary beauty,” the beauty of created things, but “primary beauty,” that of God. His writings contain no extended discussion of the nature of the fine arts or of human beauty. Even his occasional rhapsodies regarding the beauties of nature function chiefly as a foil to a deeper reflection on the divine beauty. Secondary beauty holds interest for him basically because it mirrors the primary beauty of spiritual realities.

Preaching the Beauty of God

Edwards’ focus on the beauty of God does not mean he has no interest in the beauty of this world. In his Personal Narrative, for example, while he is describing his conversion to Christianity, he indicates that his conversion wrought a change in his entire outlook on the world:

The appearance of everything was altered: there seemed to be, as it were, a calm, sweet cast, or appearance of divine glory, in almost everything. God’s excellency, His wisdom, His purity and love, seemed to appear in everything; in the sun, moon, and stars; in the clouds, and blue sky; in the grass, flowers, trees; in the water, and all nature; which used greatly to fix my mind. I often used to sit and view the moon, for a long time; and so in the daytime, spent much time in viewing the clouds and sky, to behold the sweet glory of God in these things…

This passage helps us answer the question: How does the preacher present the glorious beauty of God to His people? The answer is, not only by preaching on biblical passages that reference this divine beauty, but by taking the time to meditate on the glory of God visible in the secondary beauty of the created realm. Edwards’ sermons communicated the glory of God since they were grounded in part in his own experience of that glory as he spent time gazing upon the created beauty all around him.

What is also striking about this passage is what Michael McClymond has recently called Edwards’ “capacity for seeing God in and through the world of nature.” For Edwards, the beauty of creation exhibits, expresses and communicates God’s beauty and glory to men and women. In nature God’s beauty is visible. Thus, he could state with regard to Christ:

…the beauties of nature are really emanations or shadows of the excellencies of the Son of God.

So that, when we are delighted with flowery meadows, and gentle breezes of wind, we may consider that we see only the emanations of the sweet benevolence of Jesus Christ. When we behold the fragrant rose and lily, we see His love and purity. So the green trees, and fields, and singing of birds are the emanations of His infinite joy and benignity. The easiness and naturalness of trees and vines are shadows of His beauty and loveliness. The crystal rivers and murmuring streams are the footsteps of His favor, grace, and beauty. When we behold the light and brightness of the sun, the golden edges of an evening cloud, or the beauteous bow, we behold the adumbrations of His glory and goodness; and, in the blue sky, of His mildness and gentleness. There are also many things wherein we may behold His awful majesty, in the sun in His strength, in comets, in thunder, in the hovering thunder-clouds, in ragged rocks, and the brows of mountains.

Again, this passage is rooted in Edwards’ spending time meditating on God and Christ in creation, and his determination to have a God-centered approach to all things, in strong contrast to the man-centered perspective that was coming to the fore in Western culture in the eighteenth century.

Edwards’ Advice to Today’s Preacher

How then should the gospel preacher today speak about the beauty of God? He first needs to recognize the loss of the concept of divine beauty that is part of even his own evangelical heritage. Evangelical theologians and authors simply have not talked about beauty as a divine attribute for the best part of two centuries. Though evangelical theologians are beginning to realize what has been lost in this regard, the evangelical pulpit rarely sounds this vital note about our God. Then, time must be taken to meditate on God’s beauty in creation. Here, Jonathan Edwards is such a good model to follow: he saturated himself with God in His material world, soaking up the beauty of God displayed in manifold ways in His creation. This helped to prepare him to preach on texts that bespeak God’s beauty and glory. Of course, the biblical text was primary for Edwards. Charged with the glory of God, it provided Edwards—as it does today’s preacher—with an inerrant basis for declaring to the world this great truth: our triune God is a glorious being of such awe-inspiring beauty that the prospect of catching but one glimpse of His face in Christ in the new heavens and new earth will forever provide purpose for living all-out for Him in this world.

(This article originally appeared in the Nov/Dec 2014 Expositor magazine.)

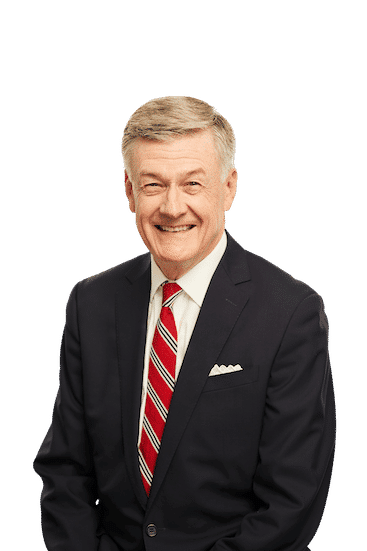

Dr. Michael A.G. Haykin is Professor of Church History and Biblical Spirituality and Director of The Andrew Fuller Center for Baptist Studies at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He is the author of a number of books, including Jonathan Edwards: The Holy Spirit in Revival and The God who draws near: An introduction to biblical spirituality.